Welcome to the last part of our sweatshops special where we talk to Punk Ethics, who run the campaign Punks Against Sweatshops, about punk core ethics, ethically sourced t-shirts and prices in the punk scene.

We do encourage you to read all three segments of the series here …

Part One: The truth about sweatshops and their relation to the punk scene

Part Two: “The priority is workers solidarity and workers power”. Interview with No Sweat.

Part Three (this one): “By keeping prices low in the West we are literally perpetuating poverty of working class people around the world”. Interview with Punk Ethics.

… and give it a serious thought. DIY punk scene has been going strong for the past few decades now and has proved many times it does not need the support of multinationals to be successful and pose threat to mainstream and the system. That said, it should be obvious to everyone that punk scene does not need commercially produced merch that is the result of workers exploitation around the world. Make punk a threat again, kick sweatshops out of the scene! Use ethically sourced t-shirts and other merch. Don’t be a dick and practice what you preach.

SP: It’s hard not to agree with what Punk Ethics say: “punk has a proud history of singing about social justice and standing up for the oppressed” and t-shirts ARE a major part of the punk scene worldwide. So why has it taken punk so long to come up with the idea of sourcing merch ethically and not using t-shirts sullied with blood and tears of the oppressed?

Punk Ethics: There is a DIY ethic in punk that is hugely important, and a big part of that is keeping things affordable, which is the right attitude, but the result is DIY punk bands are charging the same for a T-shirt at their shows that they were charging 10 or even 20 years ago, and they don’t want to put the price up as they fear that people won’t pay it, or worse they will be seen as selling out, but at the same time the cost of living for workers around the world goes up year after year, and large corporations attempts to maximize their profit means workers wages stay low. So bands look for the cheapest T-shirts available to maintain DIY punk prices, and that means sweatshop labour, and it is the workers making those T-shirts that suffer.

SP: How did Punk Ethics come about and what was the major input that made you do what you do? How big is the group and where are you based?

Punk Ethics: For years I have been involved in the UK based anti-sweatshop campaign, No Sweat, and we did regular benefit gigs, punk gigs in the 2000s to raise money for the campaign. Now there are a few punks in No Sweat, but most of the activist involved have no connection to punk, and while I wanted to carry on working with No Sweat, I also wanted to explore other issues that punk relates to. So, in 2015 I I created Punk Ethics as a way to explore other issues and joined up with friends that had organised the No Sweat benefit gigs to form this little collective. There are only a few of us, but so far we have been punching above our weight and getting different issues on the agenda of the global punk scene.

SP: I know you co-operate with No Sweat we interviewed in Part 2 of our sweatshops feature on Sanctus Propaganda. The whole campaign you run, Punks Against Sweatshops, was started in the UK where No Sweat operates. So it’s fairly easy for UK punk scene to source their merch from No Sweat, price, time and tax wise. Do you have any knowledge on other sources of ethical tees except No Sweat worldwide?

Punk Ethics: The term “ethical” is problematic. The response by capitalism to the anti-sweatshop movement around the world that has been going on since the 1990s is to create an ethical fashion industry, but this is simply whitewashing (or green washing) the abuse that goes on in garment manufacturing. A large part of ethical fashion is a connection industry that has grown alongside it, that of accreditation scheme. These are where large corporations hire companies to evaluate the factories that their clothes are made in according to criteria set by the corporations. They then use the logo of these accreditation companies to say they are “ethical”. The anti-sweatshop movement has shown conclusively that these accreditation scheme do not work in protecting workers or the planet. The exploitation and the environmental destruction continues despite what these accreditation companies claim.

So in terms of other companies that can be considered ethical, I think it all depends on what you mean by ethical. A lot of the claims made by the accreditation companies are not genuine, and where they are they simply provide evidence that the most basic laws are being abided by. For example, if you claim to be ethical but your workers only earn the legal minimum wage of their country, which across the world is not enough to live on, then your claim of being ethical is false. You are simply abiding by the law. In that instance, to be considered “ethical” you need to go beyond the basic legal requirements and pay a living wage, or supplement the workers income so that they receive an equivalent living standard to the living wage. That would be make you ethical. There are very few companies in the world that actually do this.

The best thing you can do is source from factories that are worker focused, like Oporajeo that produces for No Sweat, which is a worker initiative where the worker receive a share of the profit, or Dignity Returns, a factory in Thailand that is run as a workers co-op, or Humana Nova, a workers co-op in Croatia. It is these factories that are leading the way in real ethical garment production.

SP: It is not easy to kick out the so-called gildans out of the scene since you mentioned prices. I talked to many punks producing merch and their main argument was price of the no sweat tee. When I tell them that this is what the t-shirt SHOULD cost in reality, they just shrug their shoulders and walk away saying there is not enough margin left for them. What do you say to such people and are you often faced with such arguments? Why do punks still use gildans and what do you think needs to be done so they change their mind?

Punk Ethics: Yeah, this goes back to my earlier point, that the DIY punk scene wants to keep things affordable, but they seem to forget that by keeping prices low in the West we are literally perpetuating poverty of working class people around the world. It is not unreasonable for punks to look at what they were charging for a T-shirt 10 years ago and think about increasing their prices a little and sourcing from an ethical company. The more we fund real ethical factories that pay a living wage, the stronger the position for the trade union in the garment producing countries become in demanding a living wage for all garment factory workers.

SP: Have you come across other arguments against no sweat tees?

Punk Ethics: There are many that say sweatshops are good because it is better for workers to work in a sweatshop than starve, or be forced into prostitution or something like that. This argument is setting the bar very low. To justify exploitation, dangerous conditions (many workers around the world are injured or die in factory fires because of sweatshop conditions) because the alternative is worse is no argument at all. Some right wing economist are still pushing a “tickle down economics” idea, that workers in sweatshops are part of a country being lifted out of poverty, but the reality is corporations make BILLIONS off the backs of the sweatshop workers. If they gave them just 10 cents more that would drastically reduce the poverty level, and the extra money they earn would be spent locally, which will help benefit the local economy. There are studies that show this and it is time we take action to support this idea. Exploitation is exploitation no matter what the excuse. If you wouldn’t want to be treated like this at work why justify other people being treated like this just so you can sell a cheap T-shirt.

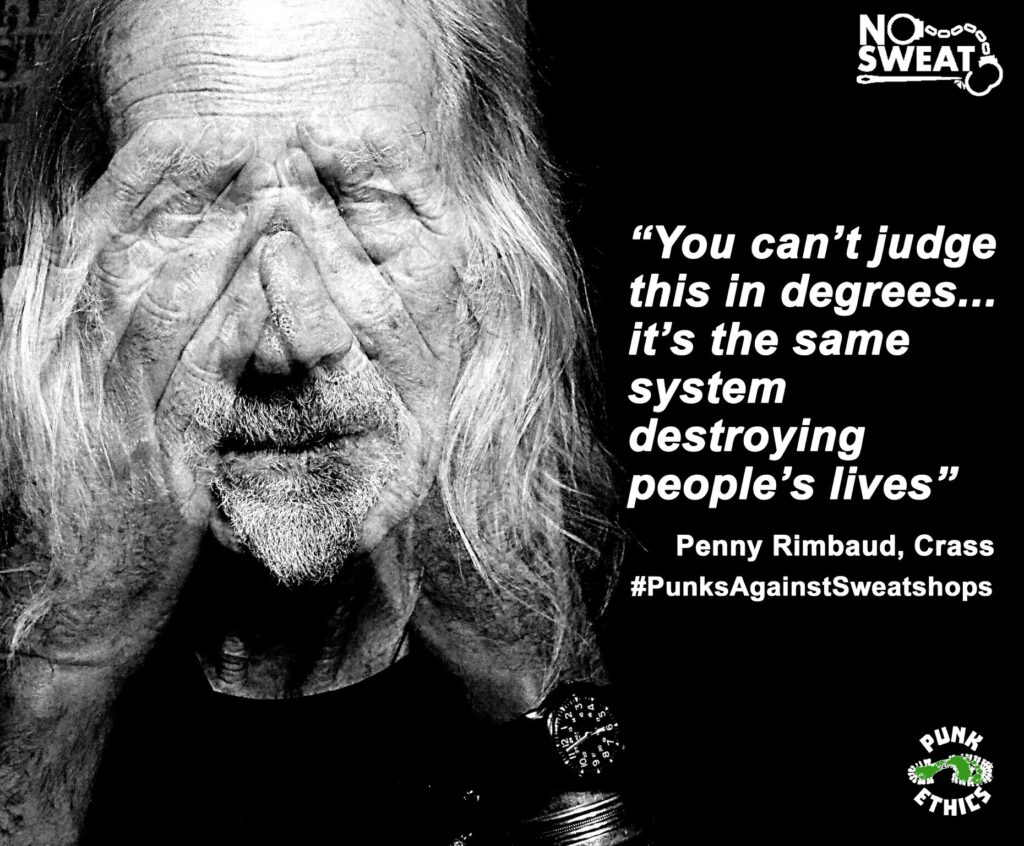

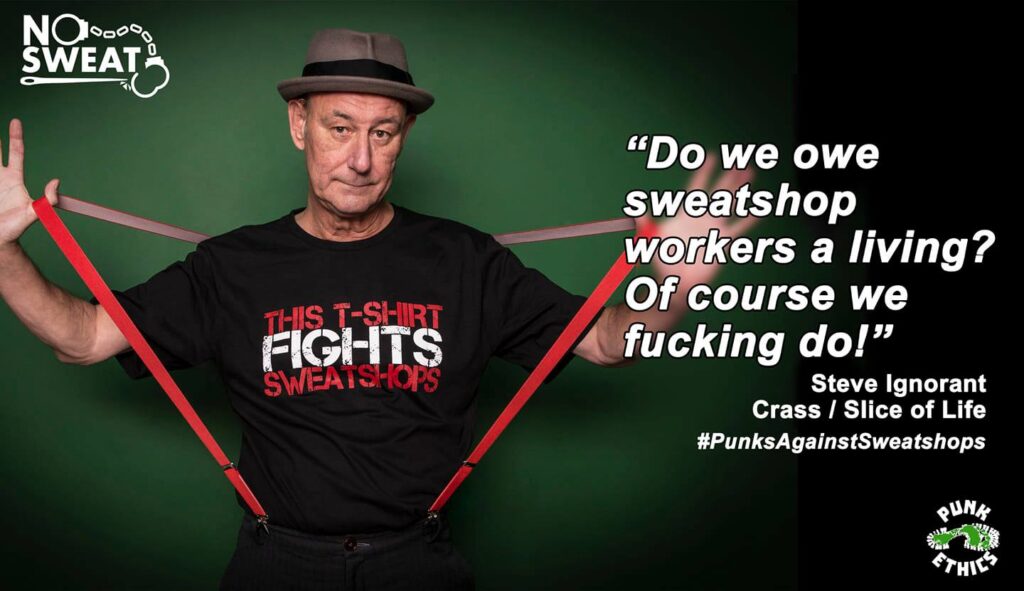

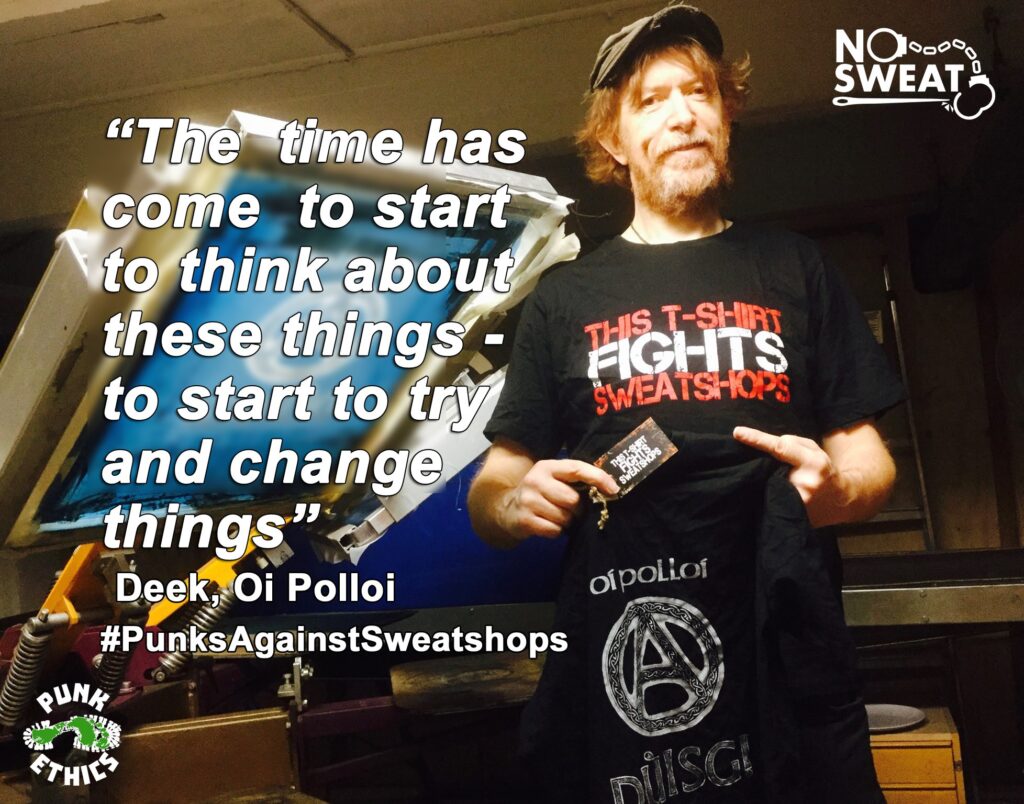

SP: To promote your idea you asked some well known people in the scene to be the voice of your campaign. How did you establish the co-operation with them? Has anyone turned you down?

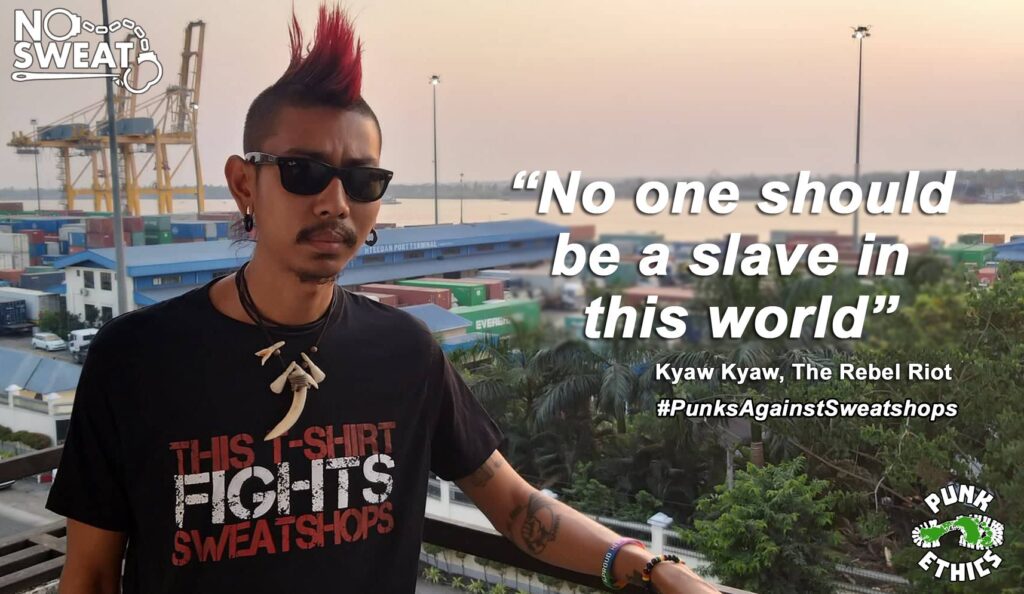

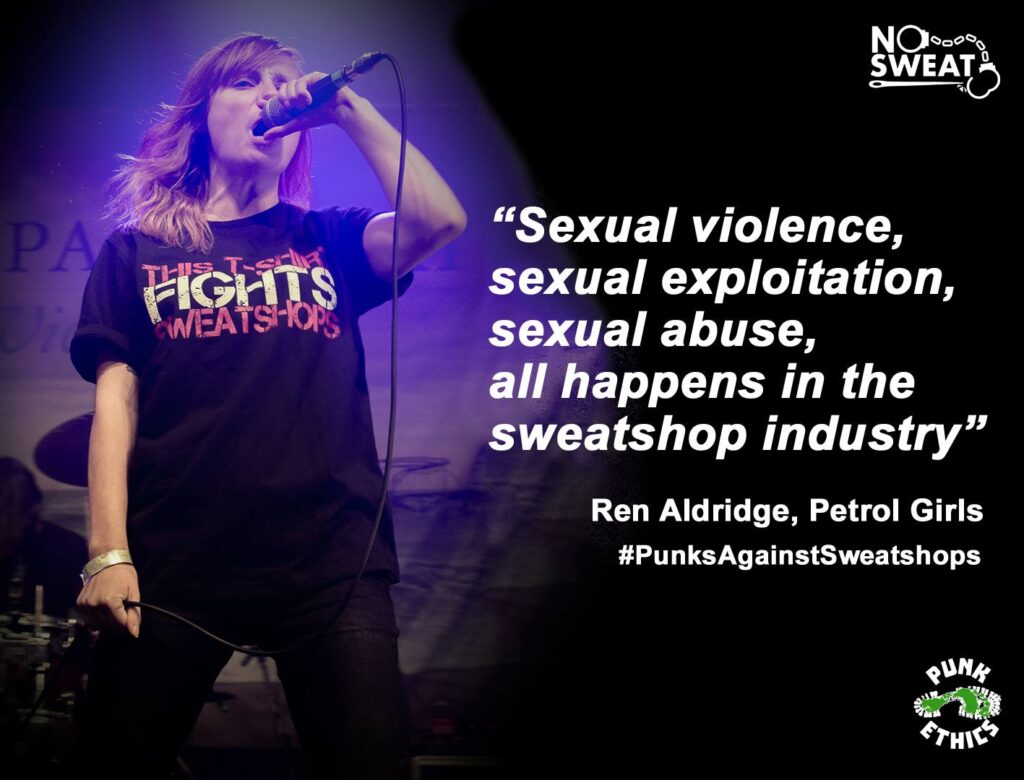

Punk Ethics: The response we got from the punks in the campaign video was amazing. No one turned us down, everyone we approached was keen to be involved, it was just a long slow process waiting for replies, arranging interviews, either in person, online, or in the case of Jello Biafra, getting them to record a piece to video that we could edit in. We can’t thank those people enough, it helped get the word out around the world, and the response from the global punk scene has been amazing.

SP: What are your plans concerning punk scene beyond UK? What successes would you say you have had so far in kicking sweatshops out of the scene worldwide?

Punk Ethics: The film has been translated into over 10 languages, all by volunteers who want to get the message out to people that speak their language, from French and German to Thai and Burmese, it has truly reached a global audience, and more language are coming through. I can’t say the exact impact it has had but it has certainly reached more people than we ever expected. One of the best stories we heard was a school, or school age group in Greece, organised a Battle of the Bands type of event with lots of teenage bands and they played the film with Greek subtitles at the event to over 400 people, this was amazing to us. I am sure there have been similar events elsewhere around the world.

SP: Do you contact labels, merch producers and bands on your own and say “look, this is our campaign, we’d love you to join it” or do you rather wait for your campaign to bear fruit?

Punk Ethics: We do that, with mixed success. After the film we decided to create a page on our website where bands, labels, promoters – any punks involved in buying and selling T-shirts, can join the campaign and submit their logo, then we put it on our website, a wall of logos of all the punks that have joined the campaign, and hyperlinked the logos so if you click on them you’ll be taken to their website or social media page. We now have over 100 logos on the website.

SP: How can bands or labels join the campaign and what support are you willing to give them in their own country?

Punk Ethics: Visit punkethics.com and go to the Punks Against Sweatshops section, there is a page on there, where you can sign up and send us your logo. If you want to show the film in your local scene we can send you a copy, and if you want to translate it into your language get in touch and we’ll help make it happen. We want to reach more and more people around the world so that everyone knows what the issue is and what can be done to change it.

SP: How much do you think Brexit and duty tax is going to affect your anti sweatshop campaign or is already affecting?

Punk Ethics: For the UK Brexit is a nightmare, it has sectioned the country off from Europe so that the UK punk scene is now forced to become more isolated. Where before we could share with friends in the EU now it all costs more. But these costs are the same for the rest of the world so I think eventually things will settle down into a new normal and the punk scene will carry on. Taxes are a fact of life, but (after the pandemic) there is always punk post to help ease the pain.

SP: To support your actions you released a nice compilation on Bandcamp. How much money did you manage to raise and where did it go?

Punk Ethics: Yeah the Give Sweatshops the Boot compilation was our way of celebrating the bands that had joined the campaign so far. We put out a record with 40 bands, agreeing that you could only download the whole album, so we didn’t benefit off any individual bands song, and we set the rate as pay what you can afford. We agreed with the bands that 50% would be used for the campaign and Punk Ethics projects, and the other 50% would be used to fight sweatshops. By the time the record came out the pandemic had decimated the garment industry in Bangladesh, so the 50% for the fight against sweatshops was sent to No Sweat production factory, Oporajeo, who had set up an emergency food ration program in their areas. The records raised 1000 GBP and we sent about 600 to them to support their project, feeding workers that were out of work with no support because of the lockdown there.

SP: Are you planning to release more compilations? Any physical formats in the planning?

Punk Ethics: We hope to do a second volume with the other bands that have join since, but we are waiting for the pandemic to be over (or get a little better) before we do it and make records. We are campaigners rather than distro people so we are not very organised when it comes to putting out records.

SP: Also gigs are a great part to collect money for your actions. Have you done many and what are you plans for post-covid (hopefully) world?

Punk Ethics: We have done lots of gigs in the past, especially in support of our friends The Rebel Riot in Burma, who run an amazing Food Not Bombs project there. We organised a tour of the UK for them in 2017, and we have a film of the tour coming out later this year.

In March 2022 we hope to put on a Punk Against Sweatshops gig at the 100 Club in London with some of the bands from the film, this was meant to happen in June 2020 and then in April 2021, but the pandemic stopped that, so we are just hoping that it will go ahead – third time lucky!

SP: Apart from the anti sweatshop campaign Punk Ethics devote their time to other activities. You work with Burma’s Common Street Punks. Tell us about this project and what have you done together?

Punk Ethics: We met them in 2014 and were really inspired by what they do. I met them in Burma and said I was heading back to London and would like to organise a benefit concert for their Food Not Bombs project and to support their scene .I asked them what UK bands would they want to see play, worrying they would say someone really famous like the Sex Pistols, but we were happy and surprised when they said The Restarts, a band we know well and are an important part of the London punk scene. We did the gig and raise over £600 which we worked out was about a years wages for a worker in Burma. We continue to support them now that there is a fascist coup in the country and keep in touch regularly.

SP: Your other activity is “Trespass” where you put on shows in the open air to reclaim public space. What gigs have you organised so far and where and have you managed to make it a regular spectacle before the pandemic?

Punk Ethics: Trespass was a special event for us. It was really the first event we did that was not a benefit for No Sweat. It took a lot of work and cost us a lot of money as it was a free event but was an amazing experience. We did two gigs, in 2015 and 2016, on the beach of the River Thames, putting on Oi Polloi and Flowers of Flesh and Blood one year and The Restarts and Conflict the next. Kim, from our collective, made two films about each that are on the website. We hoped that it would get its own life and other people would create their own Trespass events but it didn’t turn out that way. We ran out of money to do more and then just as we thought to revive it, when Boris Johnson, who was Mayor of London at the time of the first gigs, became Prime Minister in 2019, but then the pandemic hit. Who know, maybe one day! In the meantime, we encourage punks around the world to look for free space, that the public has legal access too and just put on a free show. Reclaim that space. The punks in Burma have been doing this for years as they don’t have venues they can use, we are spoilt in the West. Reclaim the streets through punk gigs!

SP: What would you say for punks to consider buying their next fruit or gildan tee? Or should you rather be talking to the producers first so they are not left with a tons of unsold gildan merch?

Punk Ethics: The Punks Against Sweatshops campaign was about starting a conversation and laying out the facts about garment production. We didn’t want to be the punk police, so we don’t have a go at people that still use the major corporate brands that use sweatshop labour, but we encourage people to look at alternatives. And if you really can’t afford a No Sweat Tee, then how about making a donation to an anti-sweatshop campaign group or a trade union in Bangladesh and making a point of telling people buying your T-shirt that that is what you are going to do. There are many ways you can make a difference, sourcing from a real ethical company is one, but shopping wont change the world we need to work together in solidarity and help build the workers movement in the countries where these clothes are made, so that they can build the power to fight for their rights, and win.