Here is the continuation of our series on sweatshops. We intend to present arguments why we think sourcing t-shirts from sweatshops in punk scene is against what punk has always been about and what should be done to change it.

In Part 1 (link here) we discussed sweatshops: what they are and what they do, we showed the alternatives to sweatshops and now we are presenting you with such alternative. Here is an interview with No Sweat – UK based project that educates on sweatshops, supports anti-sweatshop movement and sells 100% organic cotton fair trade garment sourced from a workers co-op in Bangladesh.

SP: To the readers who are perhaps new to the topic of sweatshops and the ethics of production of garments we wear, what key points would you mention we all should be aware of so we broaden our horizons?

No Sweat: A sweatshop is a workplace where workers face super-exploitation. That means long hours, working for poverty wages and working in dangerous conditions. In extreme cases this can be literal slave labour (like the situation of the Uygur people in China) or oppressive labour, where migrants are undocumented in a country and are at the mercy of the factory owners for a livelihood and possibly their living conditions, as is the case with many South Asian workers working in the Middle East, and Burmese migrants working in Thailand. Workers in all these positions face abuse in the workplace, threats of physical and sexual violence, and intimidation though threat of being dismissed and the economic impact that has or being handed over to the authorities and facing deportation. In some cases the victims in these sweatshops are children, workers under 18 that are force to work in order to support their families because of the economic hardship their parents face.

All of these practices can be found in the garment industry throughout the world. The majority of the clothes produced and sold are made by workers facing these conditions.

The key issue we promote is workers solidarity. There has been a huge rise in ethical and sustainable fashion over the past ten years or so, but it mostly amounts to corporations either whitewashing/greenwashing their existing practices, seeking accreditation logos that paint them as heroes for doing basic things like paying the legal minimum wage (which is often not enough to live on) and making sure their staff aren’t abused. Ethical fashion production shouldn’t be about covering up abuse or doing the bare minimum, it should be about changing the culture of garment production to give workers a decent standard of living, it should be about going beyond the basic minimum. There are genuine ethical clothing companies that do make a point of treating workers well and being environmentally sustainable as possible, but they rarely ever mention workers rights, and almost never mention trade unions. This is what we mean when we talk about workers solidarity.

Workers in the garment industry (and any industry) need strong trade unions, so that they have a collective voice. It is not good enough to say you treat your workers well, the workers need a democratic process to represent their interests. This means a collective bargaining agreement; workers committees to protect them from workplace abuse, forced overtime or wage cuts. In an ideal scenario it means either workers representation at the highest level, with workers elected as delegates to the board, or best of all, it means workers ownership.

Companies often fall into two categories: either capitalist that use ethical language and sustainability to improve their profits without genuine action, or liberals that make some genuine efforts to improve conditions but fail to put workers in the driving seat. We go beyond these positions and call for workers power in the garment industry.

SP: No Sweat had spent 20 years fighting sweatshop labour in solidarity with garment workers before you kicked off with your own clothing label. Can you elaborate on that period please? What exactly did you do back then, what methods and tactics did you use to combat sweatshop exploitation of workers?

No Sweat: No Sweat was formed in the year 2000, at the height of the anti-globalization movement. In the late 1990s it became known that large corporations had shut down their operations in the West and started sourcing from factories in developing countries where wages were low and conditions were poor, this allowed them to earn huge profits. So No Sweat campaigned against these giant global companies for exploiting workers in developing counties, and worked in solidarity with the workers groups in those countries that were trying to organise the factory workers.

In the UK we would organise protests outside the main stores in central London, like Nike on Oxford Street, we would organise speakers tours of trade unionist from countries such as Indonesia, Haiti, and Bangladesh, and we would organise fundraising events to send out money to independent trade unions to help them in organising workers.

SP: What milestones in fashion industry in terms of both, workers rights approach and ethical sources of materials would you mention over a period of time so we can see how things have been changing?

No Sweat: Since we started in 2000 there has been a huge shift in consciousness in the West around sweatshop labour. Most people know what it is but often don’t realize how pervasive it is throughout the garment industry. This awareness is largely down to campaign groups around the world raising awareness. A huge milestone was the collapse of Rana Plaza in 2013. Over a thousand people were killed in Bangladesh when a huge complex, housing several factories, collapsed. These were sweatshops where the conditions were poor and the structure of the building itself was unsafe. This brought the issues of the conditions of workers in Bangladesh making clothes for major Western brands to the fore, not just the wages and the hours, but the very building they were operating in. Since then there has been a huge movement to improve building safety in Bangladesh, but the problem of sweatshop condition persists, both there and around the world.

The other major milestone is the emergence of “ethical fashion” which has really appeared over the past decade. A lot of this is more focused on “sustainability” meaning environmental issues, rather than workers rights. This is largely due to the raising awareness of climate change and the ecological crisis faced by humanity. While this is a positive development the issue of sustainability is not often linked to workers rights – just because something is organic does not mean it wasn’t made by a worker suffering exploitation. In addition, large companies have spent huge amounts of money in “greenwashing” which means making an effort to appear environmentally friendly while actually continuing the same practices that damage the planet and continue to exploit people.

SP: In 2016 you established your garment production business No Sweat Ethical Trading Ltd to challenge major brands. I am guessing that you cannot compete in terms of the sales number but it was not your point I guess. You wanted to show the true alternative to ethical garment production with a primary focus on workers rights, Is that correct? How did you start, where did you go and how did you find your production partner?

No Sweat: That is exactly right. We looked at the rise of ethical fashion in around 2015-16 and noticed that a lot of companies were appearing that were marketed as sustainable but made little reference to workers rights. You’ll see some that pay it some attention but it is usually in a statement that says “we treat our workers well” or “our workers are very happy” written next to a photo of a guy in a field smiling. This is not workers rights. Since we started we have insisted that workers need their own independent trade unions, without them they are vulnerable to exploitation. So while we were still campaigning on the issue, the number of our activist had gone down over the years, so I decided it was worth trying to start our own T-shirt company that sourced from places with strong workers rights.

We started out with the idea that we would source from workers co-ops formed by ex-sweatshop workers and we would use the profits from T-shirt sales to support garment workers trade unions around the world. We felt that this would be a kind of circular economy, where the workers earn a living wage and have democratic control, and the profit will help other workers still fighting for a living wage and trade union rights.

We began working with a company in Thailand called Dignity Returns. They are a fantastic group that fought for severance pay when their factory owner closed the company overnight, and then used the money to set up their own project. Unfortunately they were not able to meet our requirements in terms of production as they mainly work for the local Thai market. Then we found Oporajeo in Bangladesh.

SP: Exactly. This is where I am going. Tell us something about Oporajeo and how the co-operation started.

No Sweat: Oporajeo, which means Invincible in Bengali, was founded by rescue volunteers and survivors of the Rana Plaza collapse. The rescue workers were members of the labour movement that had set up a fund to support the survivors rehabilitation but eventually saw that donations were not enough, the workers needed to rebuild their live and that meant earning an income. So they set up a Foundation to form a factory where the workers were declared owners and earned a living wage. The Foundation ran a few projects, including a school for their workers children. The factory itself had a traditional hierarchical structure in that there was a manager, who sourced orders etc, but the workers were involved in the decisions about the factory and they were given a share in the profits.

This model was unheard of in Bangladesh and caused a lot of tension with other factory owners at is set an example of how workers could be treated. After a couple of years, when the company was growing, the factory suddenly burned down. It was suspected to be an arson attack.

Soon after the attack the survivors of Rana Plaza finally received compensation payments, so the workers of Oporajeo left the garment industry in Dhaka and returned to their home villages.

The labour rights activists that helped start Oporajeo eventually moved to a new factory far from the place of the fire and started again. This time the Foundation was disbanded and it was registered as a private company. They had come across many obstacles in operating the factory as a Foundation, so the move to set up as a private company was a practical one. When they tried to register the new workers as joint owners they faced more obstruction. The government department refused to accept the workers as the owner of the company because they were working class – they did not have tax certificated and bank accounts and other formal documentation. So one labour rights activist registered it in his name while the workers were referred to as owners in that they still received the share of the profits, and they formed a workers committee to be involved in the decisions of the company. The workers still receive a living wage, and support with their medical bills and school fees, and they also receive a provident fund, meaning they build financial security for the future. This is all very rare in the garment industry in Bangladesh, garment workers mainly have a hand-to-mouth existence while the factory owner keeps all the profit.

While Oporajeo is not a traditional workers co-op like the kind that No Sweat had planned to work with when we first started our project, it is a unique model for a garment factory in Bangladesh, it is a workers initiative, a factory that puts workers first and profit margins second.

SP: Did it, perhaps, make way for other similar projects in the country?

No Sweat: As far as we know this has not yet happened. The experience of Oporajeo has shown that there is a lot of corruption and government obstruction in Bangladesh. The co-operative movement in Bangladesh is said to suffer from this especially, which explains why they did not adopt this model in the beginning. In the garment industry, the factories are dominated by rich owners which powerful connections in government, in many cases the owners are the politicians that make the laws. Bribery is commonplace and organized crime plays a strong part. It is incredibly hard for workers to set up their own projects in Bangladesh without support. As far as we know there are no other factories in garment industry in Bangladesh that operate anything like Oporajeo. That said, if they continue to grow and get bigger, their position will become stronger and will have more influence over the industry. Crucially, Oporajeo is pro-union. The workers have their own committees and trade unions are invited to come and audit the factory. This is completely unique in Bangladesh where trade unions face numerous obstructions from the government and threats of violence from the factory owners and criminal elements linked to them.

SP: Do you see it possible in in EU or US?

No Sweat: In the EU and the US the trade union movement and the co-operative movements are much stronger and they face much less obstruction from the government. The problem is that the cost of living in countries like Bangladesh is much lower than in countries in the EU. So to run a garment factory in the EU cost more and therefore the products are more expensive. This means the large brands that dominate the industry won’t buy from them as their focus on maximizing profits. So while there are some good companies in the EU, they can’t compete on the level of factories in Bangladesh. This is why we decided to work with Oporajeo rather than set up a factory in London. We decided that we needed to support a project in Bangladesh that can offer an alternative model to the sweatshop, and that will allow us to compete with some of the bigger companies rather than simply more an expensive brand in the UK that falls under the “ethical fashion” idea. We source from the same country as the major brands but we ensure better wages and conditions. While we are still too small to compete on the same level in terms of what we can afford to produce and how much we sell, as our project grows we can point to our partnership with Oporajeo and say this is how the industry should be run, that we have proved that it is possible and we are raising funds for the workers movement to fight to make it happen.

SP: So what’s the deal between No Sweat and Oporajeo? What is each party responsible for?

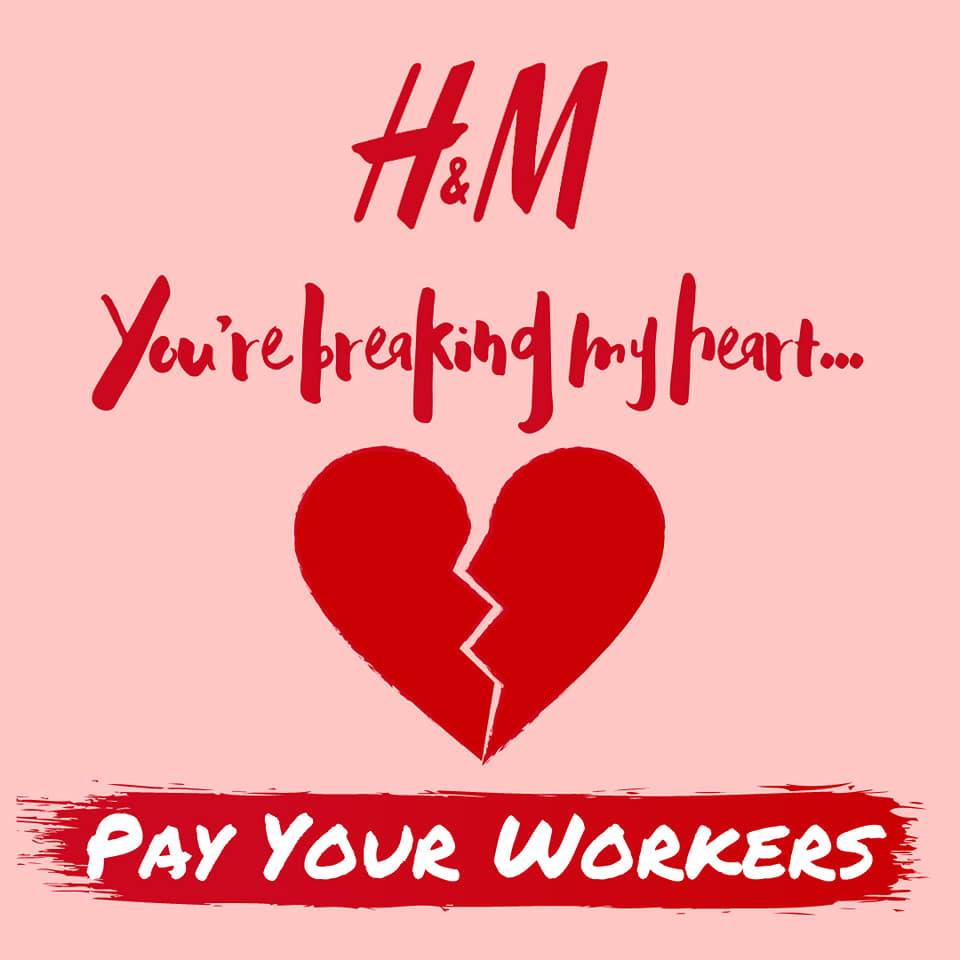

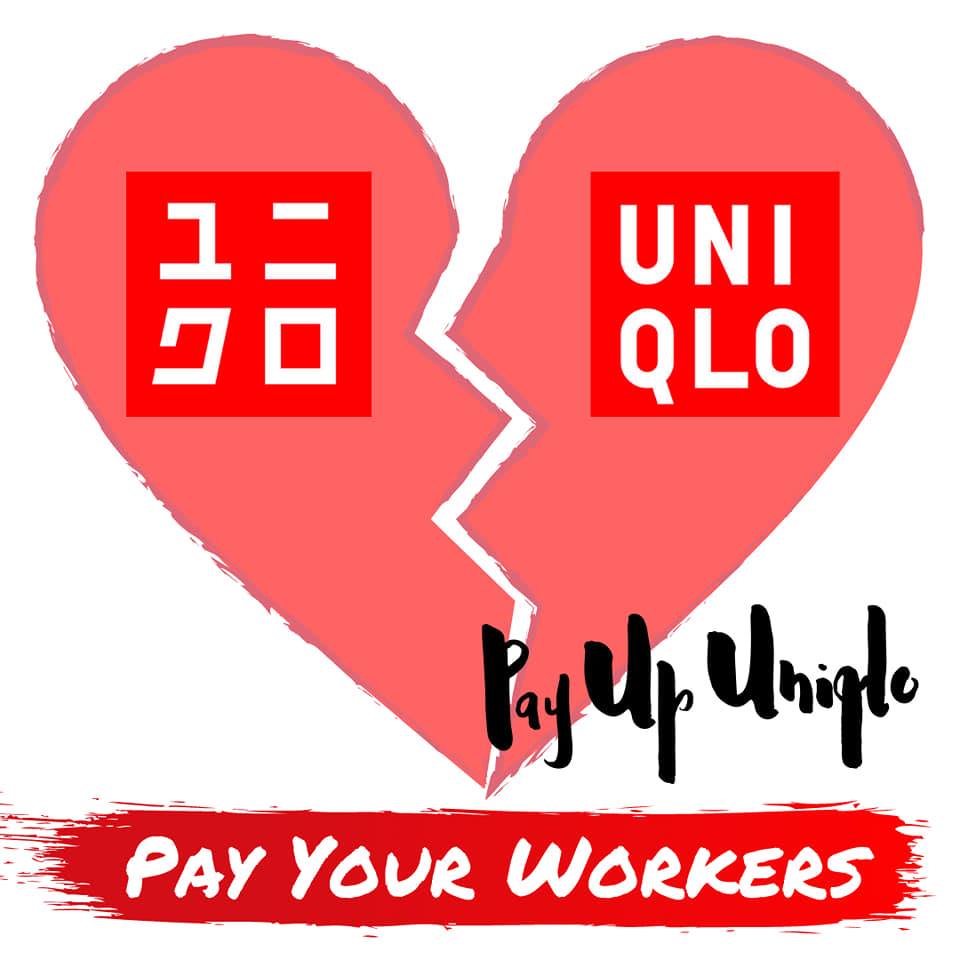

No Sweat: Our partnership is one of mutual respect rather than a literal partnership where we own parts of each others companies. We have a contract that says No Sweat will pay for the production costs in advance so that Oporajeo does not take any financial risk, which is not the same for the major brands. Large brands insist on payment after delivery and which caused a huge crisis when the pandemic hit and they cancelled their orders that had already been produced, resulting in closing of factories and workers not receiving any wages.

No Sweat pays for production and shipping and is responsible for sale in the UK and EU. Oporajeo is responsible for sourcing the GOTS certified organic cotton and producing the final product. They are responsible for the quality and the timing. We do not set strict delivery dates – this is slow fashion not fast fashion – which means that the workers do not face forced overtime but work a regular 9-5 shift.

When No Sweat sells the T-shirts we split the profit with Oporajeo 50/50. This means we are able to source the products at a cost low enough that we can compete in price with some other, larger companies, but we do not force the factory to exploit the workers, they set the rates.

No Sweat is not Oporajeo’s only customer, they are actually a jute manufacturing specialist and they make fine jute bags. This income from other customers allows them to support our project and operating with this profit share model with us without it impacting the wages and conditions of workers.

Before we share the profits, 5% from each sale is put into a Garment Worker Solidarity Fund that No Sweat is building in order to provide funds for striking garment workers. The rest of No Sweat’s profit is currently being used to build the project and will eventually be used to fund our campaign work. No Sweat Ethical Trading Ltd is the T-shirt company wing of No Sweat the campaign, and it is set up as a company limited by guarantee, which means it has no shareholders or private owners, and the profits can’t be given to individuals, it has to be used for the social good. So once we reach a point where we have enough turnover capital to buy new stock and pay workers to run the T-shirts sales, the remaining profit will be donated to the campaign, rather than taken by shareholders or owners like what happens in a regular company.

SP: Do you have any insights into other countries and sweatshop situation?

No Sweat: Yes, the situation is pervasive around the world. Wages are kept as low as possible in factories around the world so that the sale price to Western brands is kept low. This is to attract Western buyers who operate multi-nationally. Brands have the money and ability to buy their products from factories around the world and can negotiate the price on that basis. Factories cannot change the price of the fabric, they cannot change the price of the shipping, the only thing they can change is the cost of labour in producing. So Western brands force factories around the world to lower their labour costs in order to secure the contract. They save money further by not improving conditions of the factories, or hiring vulnerable people – migrants, undocumented people, children – who they can pay less. This happens around the world, and it is the brands that perpetuate this cycle of exploitation by not agreeing to pay a living wage in whichever company they are sourcing their products from.

SP: Are there many factories like Oporajeo in Bangladesh or in other countries that you know of? is it difficult to set up what Oporajeo did?

No Sweat: When we first started researching garment factory co-operatives to source from we found that there are very few. There are none in Bangladesh, and apart from the one in Thailand we only found another in Argentina. More may have appeared since but they are few and far between. The main problem I believe is this issue of price. The garment industry works on economies of scale, so the more you buy the cheaper the unit price is. If you place a small order with a co-op that is paying a living wage, the fabric cost will be expensive, on top of the labour cost. This means that sale price to the customer will be expensive which means it will be harder to sell. Now, we can’t force the factory to lower their price because it means exploiting workers, so the alternative is to buy larger amounts.

In order to grow, a garment worker co-op needs large orders so that the fabric price is lower and they can sell to the buyer at a lower price, who will then sell to the end customer for less, selling quicker and placing another order quicker. So if more and more companies chose to source from co-ops, or factories that pay a living wage like Oporajeo, then the cost of production would be cheaper for them while they are able to maintain decent conditions and wages.

SP: As far as I know Oporajeo also have some other projects to support the workers and their communities. Can you mention them?

No Sweat: Yes, they have set up something called Oporajeo Agro, which has created an organic food project to help independent farmers sell their products for a decent price, and they have set up a school and a small, ecological hydro-power plant in a rural village in the Chittagong hill. The indigenous people there are very poor, the nearest state school is several kilometers away, and there is no electricity. By building a school they have helped the children’s education and the hydro-plant (essentially a water wheel in a nearby river) generates electricity which means they have light after dark for the first time. This obviously has many benefits, one of which is some people can work after sunset in producing handicrafts which means more income for the family.

SP: Did the living wage for Oporajeo workers change because of how it operates in Bangladesh?

No Sweat: The trade unions in Bangladesh are calling for a living wage of 16,000 Taka in the garment sector. Because of government restrictions (and fear of attacks from hostile people) Oporajeo cannot pay this. The minimum wage is currently 8000 Taka while workers at Oporajeo earn an average of 11,000 to 14,000 Taka depending on skill and experience. However, the way they are able get around the law and to reach the equivalent (or more) of the trade union living wage is by providing benefits (paying medical bills, and school fees, large bonuses on religious holidays etc), which brings up the annual wage. Oporajeo calculates that for every 12 months of work, a worker earns the equivalent of 17.5 months of wages.

SP: Do you have any knowledge on how big the so-called “no sweat” business/project worldwide is? Do you know any statistics? Is there any co-operation between companies like yours who target the same enemy?

No Sweat: At the moment we are not linked with any companies around the world, and we don’t know of many that are operating in the same way that we are. We hope that this will change in the future but at the moment we are concentrating on building our project so that we can form it into a workers co-op that runs alongside our campaign. We still have a way to go.

SP: Do you consider commercial producers who value profit as their main goal your enemy OR you think a positive approach is more vital here, by showing people the alternatives?

No Sweat: It is a bit of both. On a campaign level we stand in solidarity with the workers in their struggle for better wages and conditions, and we campaign against the commercial producers that allow or encourage exploitation. That said, our T-shirt project is designed to show that an alternative is possible, while exposing the failings of the brands that say they are ethical but do not provide workers with trade union rights. It’s a balancing act between the positive and the negative.

SP: How do you find your end customers? How do you promote the idea and do you take your message outside the so-called alternative/underground market? Do you have commercial clients?

No Sweat: Because our project is a wholesale company our main clients are screen printers. We work to build relationships with more and more screen printers and merchandise companies so that they will offer our products to their clients. For the most part the underground punk scene has been a large part in building our project, this is because of our support of the Punk Ethics campaign, Punks Against Sweatshops and the campaign film they did. However we are getting more people outside of the punk scene take notice, some of the UK trade unions are starting to buy from us, and some of the larger charities. As word spreads hopefully we will be able to take more orders, which means buying more from Oporajeo, which means helping them to grow.

SP: Is the music scene one of your main targets?

No Sweat: Yes and no. We would like to build on what we have done with the punks and expand that to other genres, but we are happy to supply to anyone, whether it is a corporate company, an artistic project, a political project, or anything else. The more we sell the more we raise for the Garment Worker Solidarity Fund and the more we can source from Oporajeo, which means a larger profit share for their workers.

SP: Do you co-operate with any artists/famous people to promote the No Sweat products so there is pressure on other music companies to source ethically?

No Sweat: Kind of indirectly. We have a number of bands, like Petrol Girls and Wonk Unit for example, that have switched to No Sweat and have actively promoted the campaign, which is helping to raise awareness, but we would like to work with more bands, so if your readers want to get in touch please do!

SP: What do you think needs to be done so that workers and earth rights are respected in fashion industry? Legal regulations in all countries or customer pressure or more and more alternatives on the market that force multinational change their way of operation? Which would you consider a priority these days?

No Sweat: The priority is workers solidarity and workers power. Stronger trade unions means better conditions but also stronger trade unions means a stronger voice in calling on the powers that be to legislate for better conditions, both for people and planet. We don’t believe you can change the world by shopping, and our T-shirt project was always designed to compliment and support our campaign work, not replace it, but really we need a plural approach, more people need to do more things at all levels, that is how change will come.

SP: Tell us about your campaign for workers rights that you do except running your business. What exactly do you do and how?

No Sweat: We do many things, but we are entirely run by volunteers, so we are limited in our capacities. We try to connect with independent trade unions and workers movements around the world to support and help spread the word about their struggle. We organise protest (mostly online these days) against companies that are found to be exploiting workers. During the pandemic this has meant calling on corporations to honour their contracts and pay the factories for what they ordered so that the workers can get paid. We also build alliances with other groups to campaign together, so for example we were the group that wrote an open letter against the coup in Myanmar on behalf of the labour movement, calling on brands that operate in Myanmar to protect the workers. We managed to get this side by over 20 UK trade unions and campaign groups. We are also looking to build a UK wide network to help uncover the sweatshops in the UK and support garment workers fight for their rights, this came about following the expose of factories in Leicester making clothes for the online clothing company, Boohoo and paying workers a fraction of the minimum wage and forcing them to work during the pandemic. This project is still in the works but we hope it will make an impact.

SP: Some of the money you make on the garments Oporajeo produce goes to solidarity fund, the campaign and other projects. Can you boast any number you have raised so far to make fashion industry a better place to work at?

No Sweat: The T-shirt project provides a small donation from each sale and No Sweat fundraises more to increase the fund. We raised 5,000 GBP at the start of the pandemic and sent it to Oporajeo who set up an emergency response project when Bangladesh went into lockdown, providing free food to thousands who suddenly found themselves out of work. So now we are starting again to rebuild the fund. We have a donation button on our website that people can donate to. We have no paid workers so 100% of the money goes to worker solidarity.

SP: How environmentally friendly are your garments? Was that also the key objective for Oporajeo to make such products in Bangladesh?

No Sweat: All our products are GOTS certified organic and the factory is carbon neutral as they offset their emissions with a tree planting project as part of their Oporajeo Agro project. This is important to us but we try not to over emphasis this like some companies. At the end of the day, making clothes takes a lot of water, they are made (or the fabric is grown) far from the end customer, this means they need to be shipped around the world and the shipping industry is a huge emitter of carbon. Any company that claims their clothing has some sort of earth-positive effect is talking nonsense, the best any clothing company can claim is they are doing their best to minimize the damage their clothing production is having on the environment. They truth is, is the major western brands made genuine efforts to minimize their impact both environmentally and socially, the world would be a lot better off.

SP: How much did the pandemic change the situation for both no sweat garment market and the commercial one? Can you compare and contrast or both were affected in the same way?

No Sweat: The pandemic has had a huge effect on the garment industry. As I said before, millions of workers have been robbed of wages by large corporations cancelling their orders. There is now the onset of economic problems caused by the global lockdown. The price of cotton has increase dramatically this year because of poor yield meaning short supply, and less people manufacturing while in lockdown. The price has increased by approximately 25% while the brands are only offering a 5-10% increase to the factories, That means wages will be pushed down further.

SP: Can you see any disruptions in your commercial operations because of Brexit?

No Sweat: Yes, there has been huge delays to orders that we send to customers in the EU, and they are now paying taxes that they were not before, so the end price is higher than it was before Brexit. We are thinking to set up a connection in the EU and have shipments go direct to them, so that EU customers don’t suffer delay and increased costs when buying from us. Ironically, this was the government’s official advise after Brexit when everyone saw what was happening. The government that created this mess because they wanted to get out of Europe is now telling UK companies to set up business in the EU!

SP: Is there any documentary you’d recommend watching on the topic of our talk here or should you make one for Netflix?

No Sweat: Maybe one day we will be able to tell Oporajeo’s story in a documentary, we’ll have to wait and see. In the meantime they were featured in a BBC documentary about Rana Plaza called Clothes to Die For, I’d highly recommend it to anyone if you can find it online

SP: You say that “only standing in solidarity with the workers to put pressure on brands and governments to make the changes they demand will end the exploitation of the sweatshop industry”. How can customers like you and me do it?

No Sweat: Apart from buying a No Sweat T-shirt the way to do it is support the campaigns that are working in solidarity with workers. After you’ve bought a No Sweat T-shirts, go online and tell the world about it, spread the message when we (and other groups) report on trade union activity in Bangladesh and other countries and help us fundraise to support their work.

SP: How do you see the future of fashion industry in relation to ethics in, say, 5 years time?

No Sweat: I hope that things will change but it is going to take a huge effort at many different levels. I don’t want to try and predict the future, at the moment it doesn’t look good, but in the words of the IWW hero, Joe Hill, “don’t mourn, organise!”